That sounds like a good name for a rock-and-soul band, doesn’t it? “Big Buddha & the Bell of Time”, Japan Reunion Tour 2025! Get your tickets now!

Well, it’s not a band — although a mischievous voice in my mind keeps inventing potential hit titles: Let’s Get Existential; I Don’t Care Anymore (There’s No One to Care Anymore); Another Want Bites the Dust; He Ain’t Nihilist He’s My Buddha; and of course a fresh cover of Steely Dan’s 1973 classic, Bodhisattva.

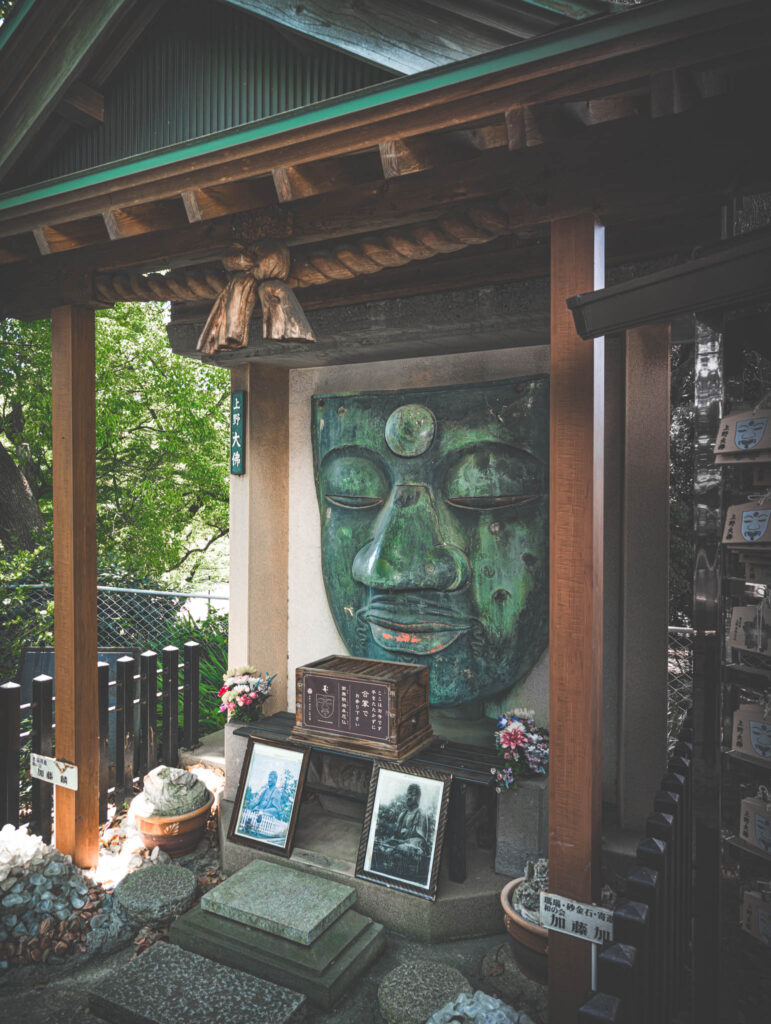

Of course, I actually am writing about the Ueno Daibutsu, which isn’t so much a Big Buddha as what is left of one, the 1631 disaster-buffeted bronze that was finally and permanently toppled by the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923. The great body was melted down during World War II for armaments — not quite the dissolution for which the karma-weary would hope. But the face of Sakyamuni remains gently smiling in its little shrine next to a stupa under messy renovation at the top of a hill in Ueno Park, Tokyo, and I went there because Atlas Obscura told me to.

While I was standing there wondering what I thought about this, I realized that just past the Enlightened One’s right cheekbone I had a clear view of Ueno’s Toki no Kane (Bell of Time), less than two hundred feet distant with the platform of its tower at approximately the same elevation as Buddha.

The Bells of Time, which sounded (and some of which still sound) the variable hours of the Shogun’s city, are finally — all these years after the Tokugawa bakufu fell — having their moment (har har). I believe that this is partially the result of author Anna Sherman’s deservedly popular memoir The Bells of Old Tokyo (2019), which brought (or restored) Tokyo to its rightful place among the other great cities like Paris, New York, or Venice in the Firmament of Thought-Provoking Metropolitan Melancholy.

I heard the Bell mark noon not long afterwards as I was following my phone’s guidance to the Ueno Park Starbucks for some refreshment. (Thanks to Google, you can hear the Bell too <link>.)

I also suspect that the Bells have become popular because of a quirk of language, manifested in the English name for them. The phrase bell “of time” not only implies that the Bell is associated with time and the marking of time, but might also be read as indicating that the Bell is composed of time itself (as opposed to ordinary verdigris-tinted alloy), in the same way as man “of flesh and bone” suggests my qualitative makeup.

The notion that a physical, audible artifact might be presumably composed of crystalized time is a most boggling and attractive one. And how do we know it’s not true?

Leave a Reply