After a long day of seeking out sites for the seeing, I was hurrying through Azabudai, trying to beat the twilight and find a Uniqlo where I could buy a hat for tomorrow’s traipsing, because the Tokyo sun really had begun to turn my head an embarrassing pink. And I suddenly found myself confronted by a couple of buildings that I recognized as (after a fashion) masterworks, both tied to a professional who might have been considered a minor starchitect in his own country of Japan, even if he isn’t well-known in the West: Shirai Seiichi (白井晟一,1905-1983).

The first is the Reiyukai Shakaden, a pyramidal metal-clad 1975 temple for a well-known philanthropic Buddhist lay organization. The design, as well as the construction, is attributed to the Takenaka Corporation, an architecture-engineering-construction company founded by a shrine-building former vassal of the warlord Oda Nobunaga in 1610 (which, incidentally, has to be the Most Japanese corporate foundation story I have personally encountered). The design team was led by Kenichi Iwasaki, not Shirai Seiichi, but multiple websites either suggest the opposite or assert that the Takenaka designers were influenced by Shirai’s ideas or theory “of the bizarre” (an epistemological framework I have yet to track down, if it exists at all) <link>. I was given a quick tour of the temple by a lonely-seeming and English-speaking security guard. The interior, which is not to be photographed, is as deliberately, luxuriously unfamiliar as the exterior. Except for the statue of Shakyamuni, it would be hard to interpret this as a Buddhist religious edifice, or really as any kind of conventionally-programmed architecture.

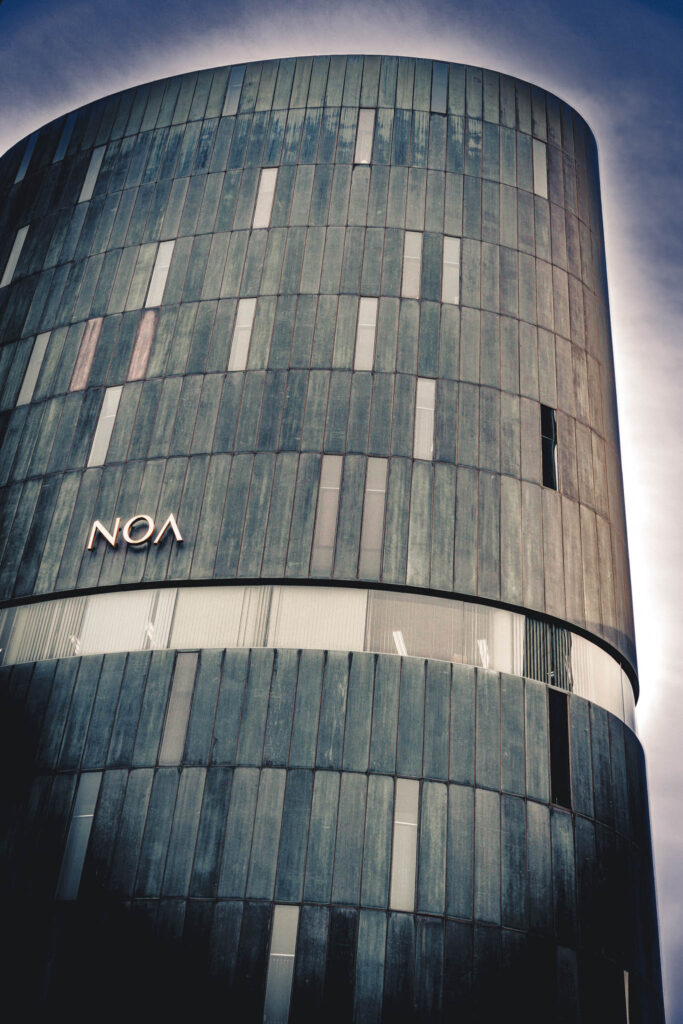

The nearby NOA Building, a 1974 office tower with a variety of tenants including the Embassy of Fiji, is however undeniably the design of Shirai. Its dedicated website <link> notes that the site owner was introduced to Shirai by the owner of Takenaka Corporation, and Takenaka went on to realize Shirai’s scheme. So it is not inconceivable that Shirai had more than a little influence on the temple’s contemporaneous design. Also (and let’s face it) the two buildings do seem related, by sheer bizarreness. Neither of these edifices actually indicate outwardly what they are. The temple could be a spaceship, the office building a techno-warlord’s fortress — except that neither seems to be futuristic any more than either seems the product of the 1970’s in Japan, Eurasia, or anywhere.

So, who was this man who designed such mysteries? To put it succinctly (and there is no other way, as my Japanese is most limited and there is almost nothing accessible for the non-Japanese-speaking available concerning him other than some abstracted summaries of his opinions), Shirai was a young man who went to Kyoto Craft School and then went to Germany between the wars to study philosophy and then came back to Japan and then decided to be an architect.

Subsequently, he memorably stirred the goldfish bowl of mid-century Japanese architectural debate over the correct “path forward” for twentieth-century Japanese architecture: “tradition” (i.e., the imitation, at different levels, of the seventeenth-century sukiya Katsura Imperial Villa) versus (European neo-Corbusian) “modernism”. Instead, proposed Shirai, why not the consider “Jomon style” versus “Yayoi style”? The Yayoi rice-growing settled agriculturists were doctrinally assumed to be the progenitors of the modern Japanese, displacing the earlier semi-settled aboriginal (and maybe not-very-Japanese) Jomon hunter-gathers sometime around 300 BCE in most of the Japanese archipelago.

This reconceptualization of the tradition-versus-modernism debate seems to have dropped onto the mid-century post-war architectural establishment like a depth charge and is consistently quoted and studied by younger architects. But did Shirai mean it? Later Shirai writings, judging by the few summaries I can find in English, seem to be more conventionally if quixotically ethnopartisan (asserting the primacy of Japanese tradition, for instance, through the metaphoric comparison of chopsticks versus Western spoons — which is very odd, since the fork was really the indelibly-Western eating utensil, and Shirai having lived in Europe would have known it). Soon enough it seems that he entirely abandoned Japan-specific traditionalism as motivation for architectural design in favor of a sort of East Asian (i.e., generally Chinese) and later Asian or Eurasian pan-traditionalism, whatever that means (or doesn’t) in its all-encompassing generality.

Architectural Theory (capital-A, capital-T) has always been and forever shall remain a form of sophistry, an organizational scheme amounting to a complex gimmick that designers use to convince themselves (and, more importantly, their clients and anyone else capable of a responding with a forceful No! when confronted by a design proposal) that there is a basis other than whim or arbitrary personal preference for any particular architectural artifice. That any non-structural decision matters more than any other, that one thing didn’t simply lead to another

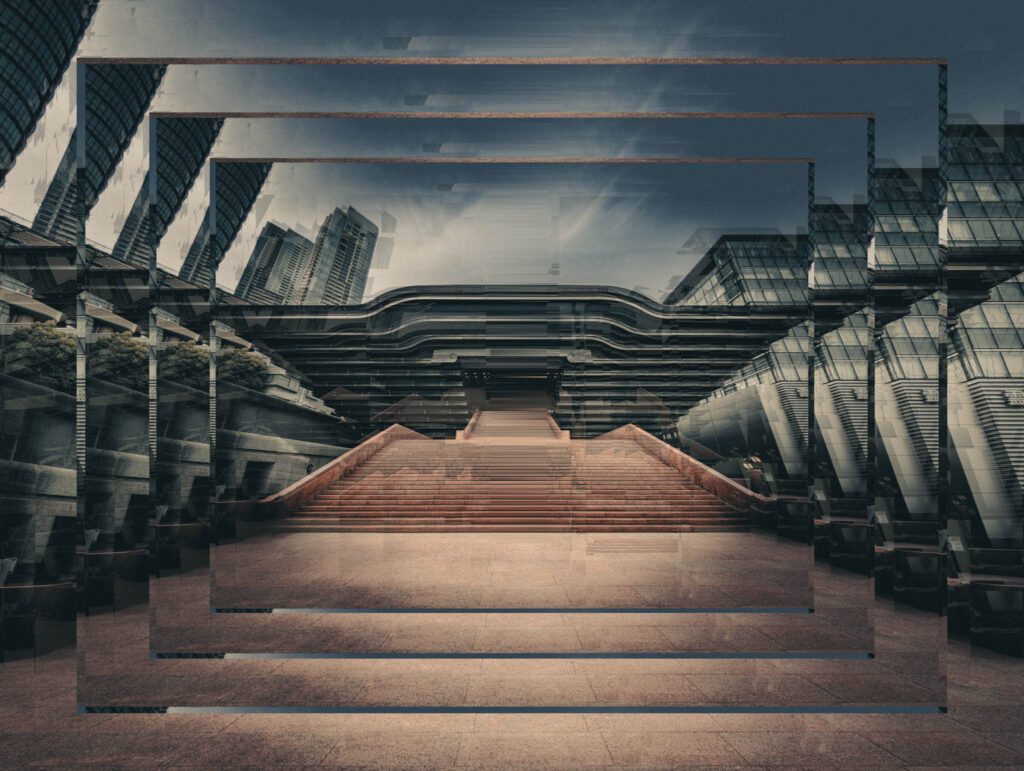

But what was Shirai’s personal preference in design? And why? His work (and I am judging it by photos and drawings in books that I cannot easily read) is consistently characterized by a kind of marmorial stillness and shadowy monumentality, approaching deliberate emptiness and the purely ominous — that only seems remotely “Japanese” if one is a junkie for Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows.

Otherwise, his designs seems to verge on de Chirico-like metaphysics and somber Classical (Greco-Roman) motifs, only minus of course the obvious Columns and Orders. And in fact Shirai did like his Latin inscriptions (note the “NOA SUM SALVATRIX” scratched into the very-abstracted Jizo sculpture high on the brick plinth of the NOA Building).

But most importantly, Shirai’s work seems to have a a slightly uncanny quality, as if they (or at least their designer) dropped out of a parallel but quite different reality. Now if only there was a conceptual architectural theory to account for that, to explain that sense of “another reality” — as opposed to dismissing it as the product of eccentric whims of one very particular and peculiar person!