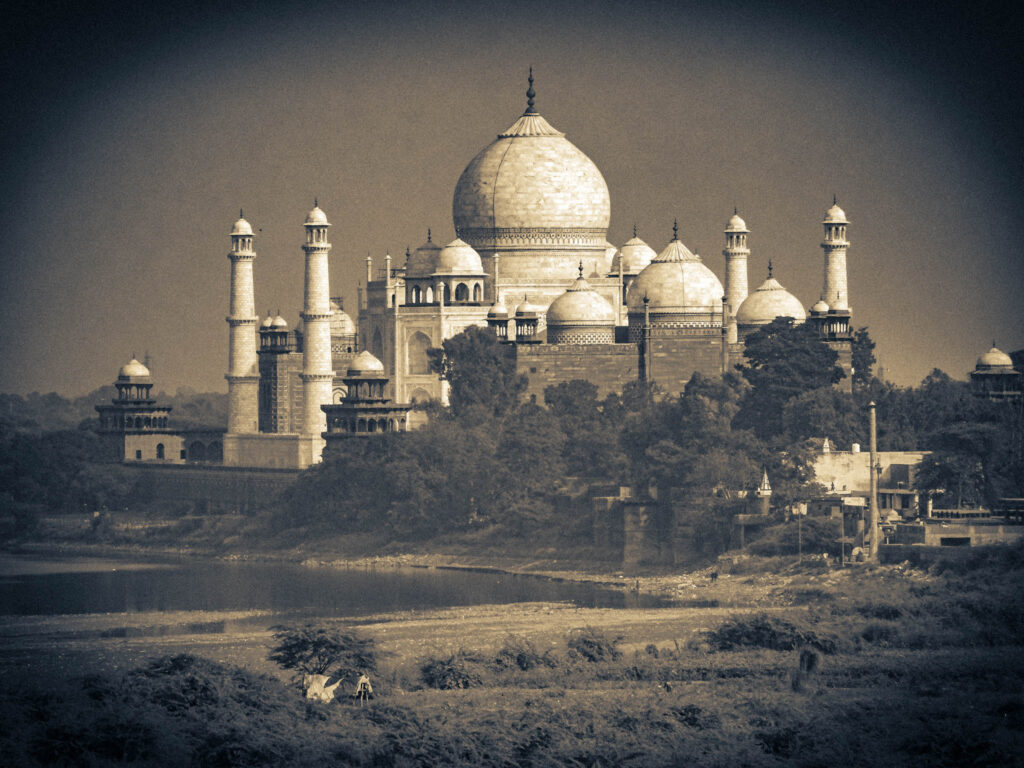

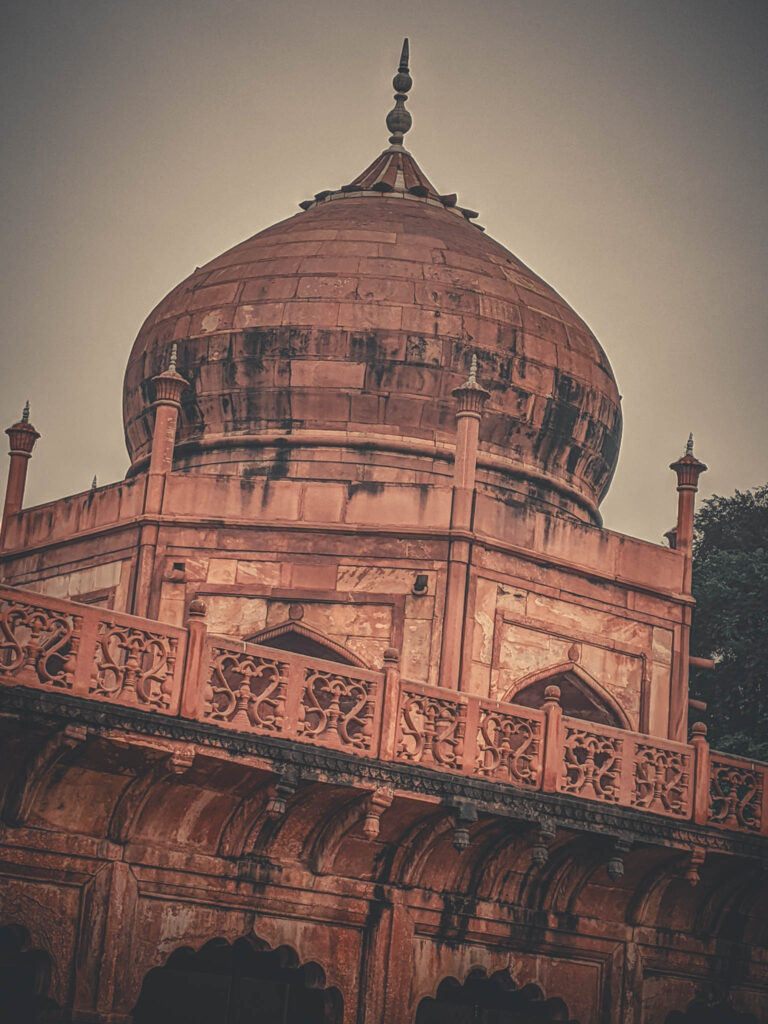

The first set of the photos below are from the day before I visited the Taj, when I tried to capture a view similar to that the imprisoned emperor Shah Jahan would have had of his consort’s tomb from his confinement at Agra Fort.

So early in the morning here I was, standing in already-long lines with the other tourists to buy a ticket and go through a metal detector (there are metal detectors everywhere in India). A dim yellow blotch low on the horizon was rising slowly through Uttar Pradesh’s yellow-orange-and-somehow-green autumn mist (or rather, smog, from the burning stubble and other rubbish in Indian farmers’ fields). The world smelt like cooked plastic. A woman that I knew on the tour — who traveled inexplicably with plush toy animals that she photographed in front the famous monuments wherever she went — was angrily arguing with the armed guards and refusing to enter if her stuffed rabbit couldn’t come with her. I briefly considered the possibility that they might shoot her as a potential terrorist.

I was also wondering why I was there. Sweaty tourists, bored guards, restrooms that make one gag, searches and regulations, mad dogs and Englishmen. I own multiple well-regarded texts on Mumtaz Mahal’s sumptuous final resting place, and I will not in my allotted time ever be able to improve on the artistic or informational qualities of the photos and illustrations therein.

In some ways, it would be more interesting (at least in terms of unique experiences for the traveler) to explore the strange neighborhood to the south of the Taj’s current forecourt, a disordered cluster of buildings that organically over the centuries grew like inhabited vegetation across the carefully-planned Chauk market and caravansaries that the Padshah originally designated as the commercial zone for the complex. That’s just a fantasy of course. It seems (correctly or not) alarming and possibly dangerous to enter such places in India without company. One will be swarmed by people who want photos-with-foreigner or who want to drag one into dark cramped stall-stores selling poor copies of items that one will never need or who simply press grubby business cards (which recommend that “For All Telecommunications Needs PLEASE TO TELEPHONE AT ONCE” or something equally unlikely) into one’s hands. The desperation gets out of control quickly.

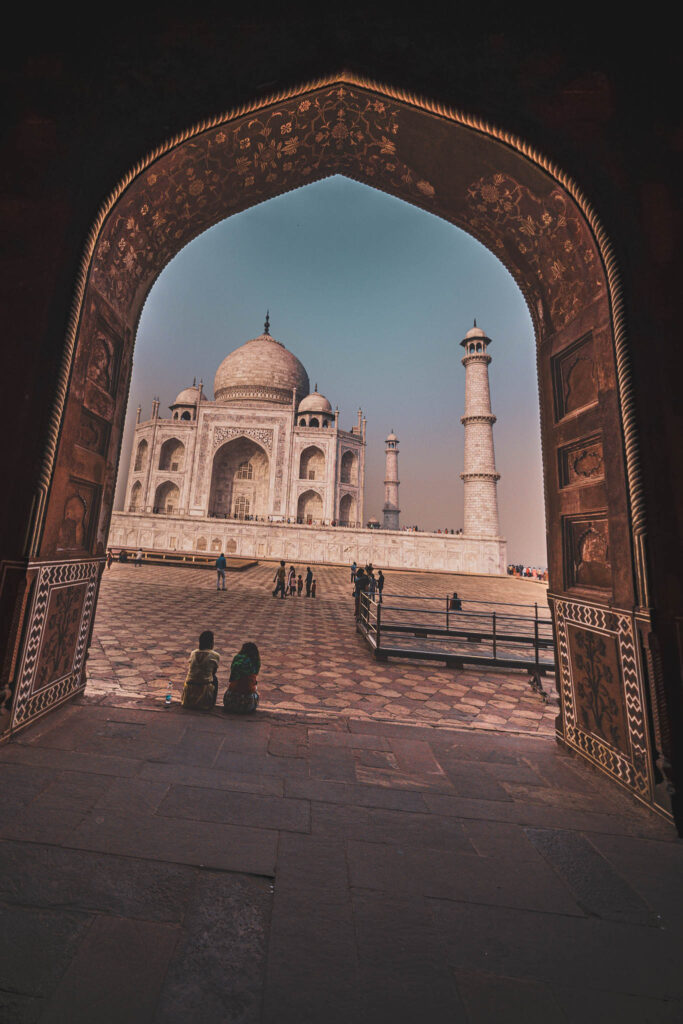

I was and am probably being unfair to the inhabitants of the Chauk, which could be simply a charming and picturesque Indian business district. I was also becoming ill, despite my best hand-sanitizer-efforts, and I’m sure the pathogen was coloring my perceptions and imagination already. Dysentery. I would be in the throws by nightfall and wish I was dead by the next morning. So when I popped like a cork from a bottle out of the crowded tunnel of the Darwaza-i rauza (Great Gate) into the charbagh four-square Garden-of-Paradise fronting the mausoleum proper, for a moment I didn’t understand where I was.

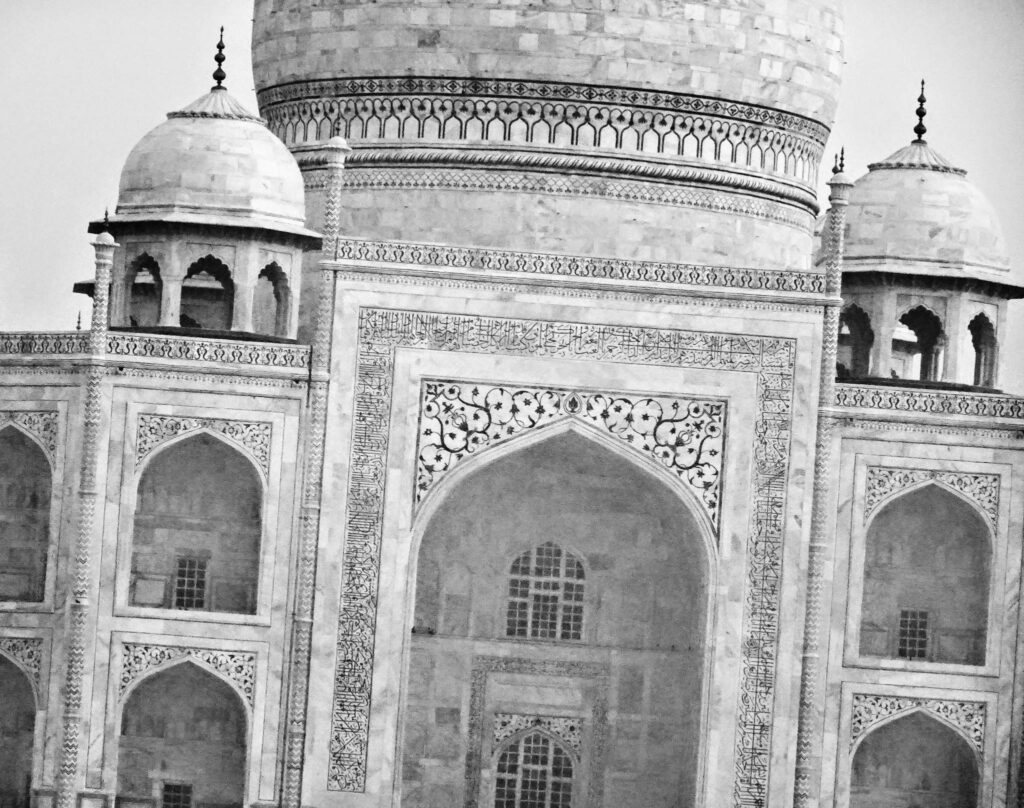

Now I know that — at a certain point — I put on the silly paper booties, stood in line once more, and filed under the great marble pishtaq of the mausoleum. I also partially remember trying and failing to successfully toss a few rupees, as recommended, into the open container placed for that purpose in front of the marble-screened imperial cenotaphs, thereby earning a contemptuous glare from the bearded attendant. But the visual component of those memories is largely missing. I might as well have deliriously crawled up into the great hidden netherworld between the mausoleum’s high outer and low inner domes and partied in the dark poche space filled with bats and corrosive guano that I once read exists there. Pardon me, mind if I hang here? Thanks! Some more fermented fruit pulp for me? Don’t mind if I do! Cheers! or rather squeek squeek squeeeek!! How long until twilight?

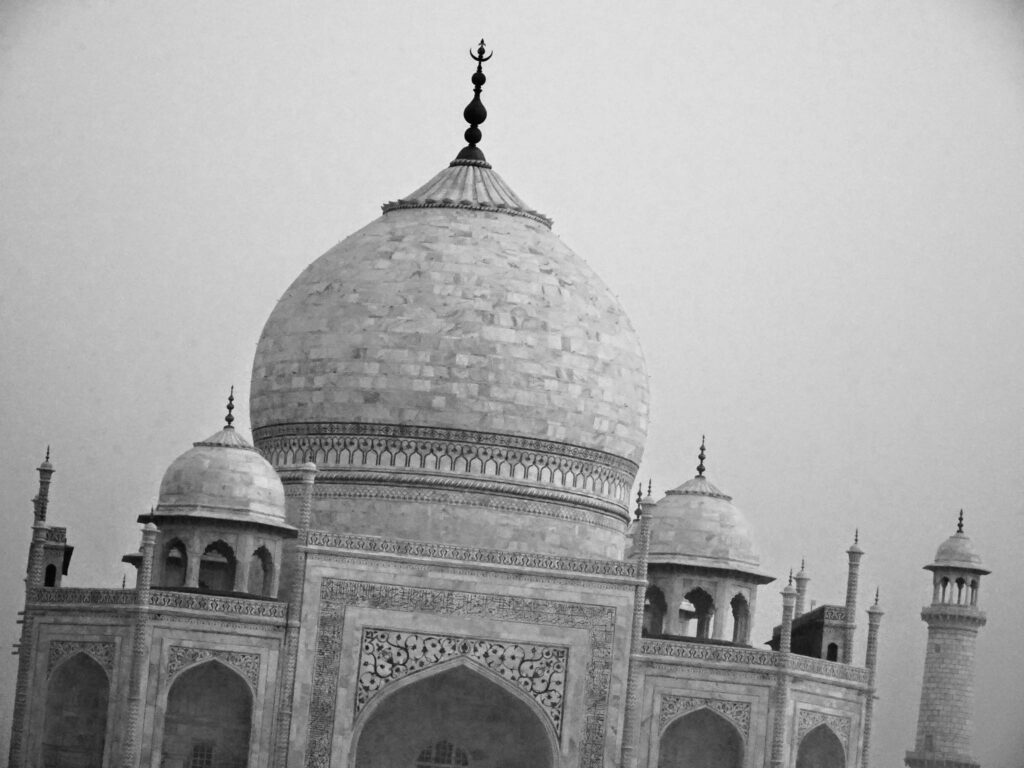

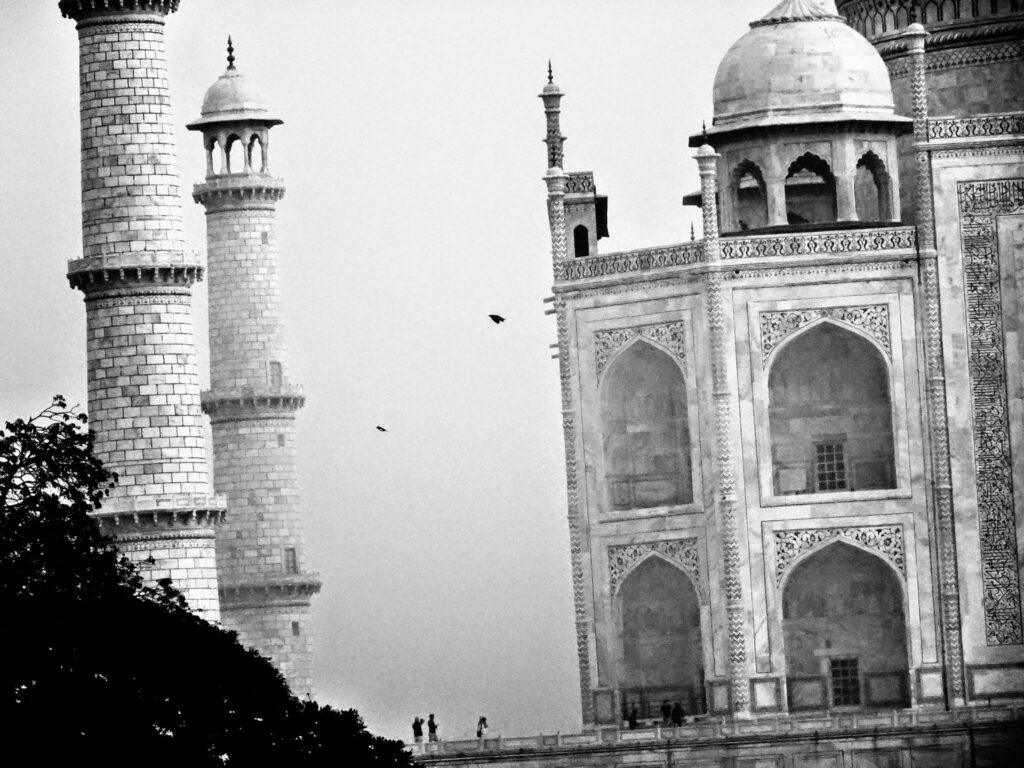

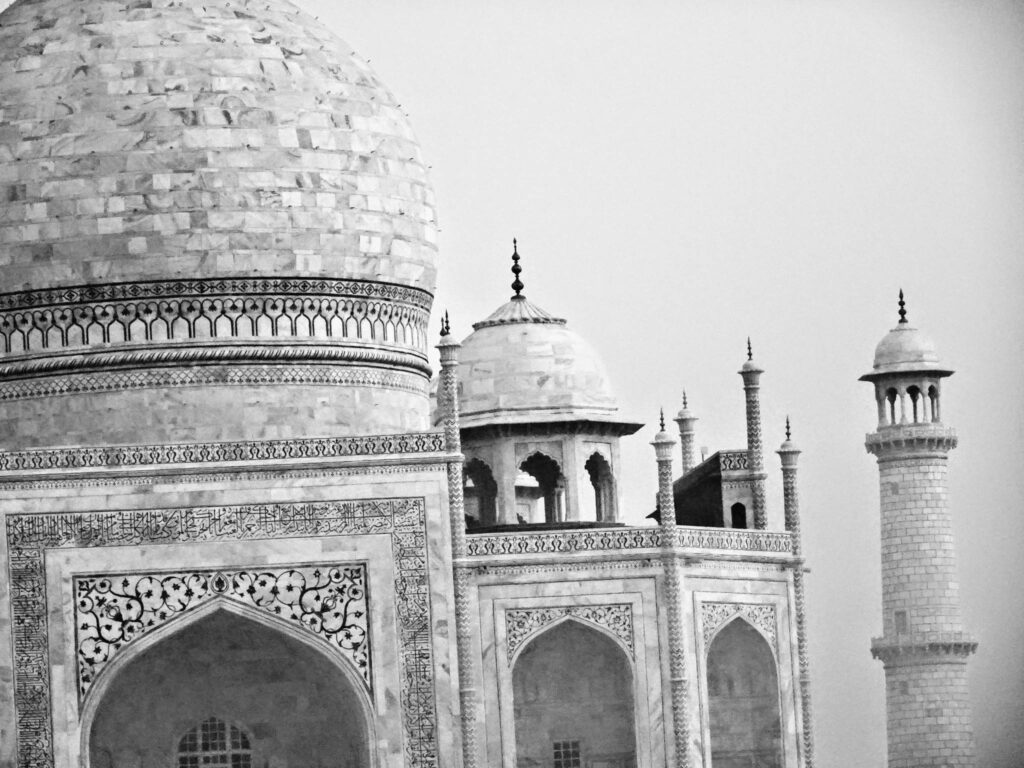

And then I was out again in the somewhat-more-obvious sunlight, in an architect’s purgatory staggering round and round the perfect marmoreal proportions and glorious intarsia of the mausoleum as the colors in the sky become slightly more believable — noting the odd boat drifting without ripples down the mercury-limpid and mercury-polluted Yamuna beyond the balustrade — taking photographs from increasingly portentous angles of other tourists themselves taking photos in increasingly portentous poses — until the appointed hour arrived when our guide would meet us with the bus outside the crenelated walls.

Leave a Reply