And that is how, with something of intellectual’s sneer, I described the Breakers (1895) and Marble House (1892) to my thoroughly-bored youngest, when we toured the grand Vanderbilt “cottages” these two days of her precious spring school vacation.

That was my first reaction on visiting the palatial “cottages”.

Almost immediately, I caught myself and began reconsidering that summary dismissal, which (if I think of my own personal history, growing up as I did on an architecturally-lesser, somewhat-more-run-down Gilded Age estate in the South) strikes me as a conditioned response somehow inculcated in me during my education.

There’s nothing wrong, by themselves, with houses like this. From personal experience, I can attest that it was actually somewhat great to be a kid with the run of a largely abandoned, relatively-grand 19th-century hunting lodge, filled with some dead wannabee-aristocrat’s bric-a-brack and Victorian cast-offs. It nearly made up for an incredibly isolating and peculiarly lonely childhood, in fact!

And actually, what do architects do, after all? I often find myself thinking about an instructor’s matter-of-fact, unapologetic reply, when I was at Yale School of Architecture and another student asked what sort of work he did. “I design houses for rich people.”

Of course, that begs the question: could architects do something else, design for someone else?

Here in Newport, were Alva and Cornelius II and William Kissam and their various descendants and relations that bad, to deserve damnation due to their extravagance in interior decoration and the net residential square footage of their domiciles? They certainly weren’t as immoral (or even potentially inhuman) as the current crop of nepo-babies, oligarchs and tech lords, in any case, and certainly (unlike the modern ilk) unlike to literally destroy civilization out of greed. Although the Vanderbilt failings and foibles were certainly magnified by wealth and celebrity, they were born or blundered into their positions and yet longed for more like everyone else, and ultimately died — like everyone else.

Much you had of land and rent; Your length in clay ’s now competent: A long war disturb’d your mind; Here your perfect peace is sign’d. Of what is ‘t fools make such vain keeping? Sin their conception, their birth weeping, Their life a general mist of error, Their death a hideous storm of terror.

— John Webster (The Shrouding of the Duchess of Malfi, 1623)

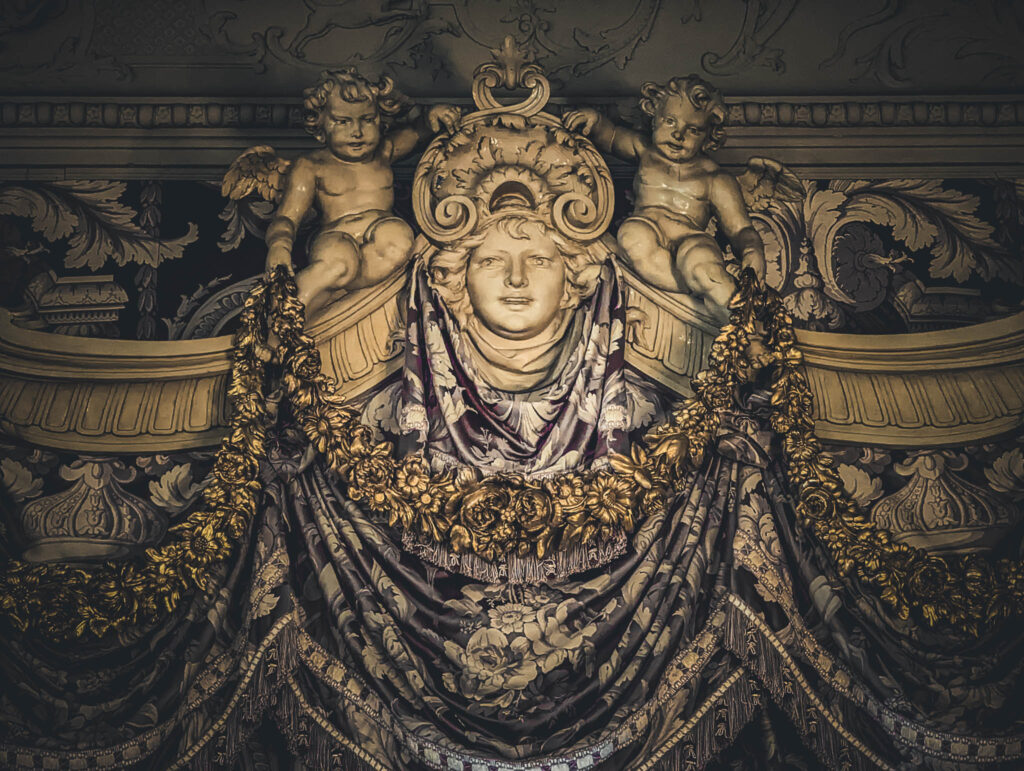

At least Commodore Vanderbilt’s grandkids left the houses for (ultimately) others to admire. Also, my high-hat reflexes aside: there is a quirky melancholy, or even a hint of damnation, in all these gloriously-proportioned and gilded chambers. Faces painted, cast, or carved — many of them smiling but others grim or despairingly lost — are everywhere, leaning out from frames or urns or light-fixtures. And the mirrors! In the reflections it seems my camera caught a more desolate version of reality, cracks in the plaster, rich tints fading to powdery-pastels, spaces as empty and lonely as a foreclosed ruin. This odd sepulchral tinge — was it always there? Does it just “come” with the over-the-top Beaux-Arts? Or did it accumulate over the brief century of Vanderbilt decline since?

Or did architect William Hunt Morris, interior designer Ogden Codman Jr., and decorators Jules Allard et Fils pick up on the inevitable dissolution of client and commission — and somehow bake the elegiac ambience into the plans and furnishings? I can’t help but wonder if these design professionals, acclaimed in their own time, had a better understanding of their ultimate brief than that for which they are usually credited. Neither the Breakers nor Marble House are owned by the family that commissioned them; a not-for-profit scrambles to maintain these massive piles.

For most purposes after all, the two mansions have been something other than residences for much of the last century.

Leave a Reply