Meanwhile, impatient to mount and ride,

Booted and spurred, with a heavy stride,

On the opposite shore walked Paul Revere.

Now he patted his horse’s side,

Now gazed on the landscape far and near,

Then impetuous stamped the earth,

And turned and tightened his saddle-girth;

But mostly he watched with eager search

The belfry-tower of the old North Church,

As it rose above the graves on the hill,

Lonely and spectral and sombre and still.

And lo! as he looks, on the belfry’s height,

A glimmer, and then a gleam of light!

He springs to the saddle, the bridle he turns,

But lingers and gazes, till full on his sight

A second lamp in the belfry burns!

Or so versified my Possible-Cousin in 1860, thereby elevating an obscure Colonial silversmith to the rank of master patriot. P-Cousin Henry Longfellow (as I recall) was a financial backer of the Underground Railroad (good for him! my direct Wadsworth ancestor and Longfellow’s contemporary was most definitely and discouragingly not an abolitionist), and Henry wrote on the eve of the American Civil War with the goal of rousing his fellow citizens to face the coming crisis:

In the hour of darkness and peril and need,

The people will waken and listen to hear

The hurrying hoof-beats of that steed,

And the midnight message of Paul Revere.

Paul Revere’s Ride was published in January 1861 just as South Carolina seceded.

There’s a lantern (but just one and a duplicate of the surviving original of the famous pair) mounted in an old window looking out into the nave, to the side of the apse — a leftover from the Bicentennial and a visit by President Ford. High ho.

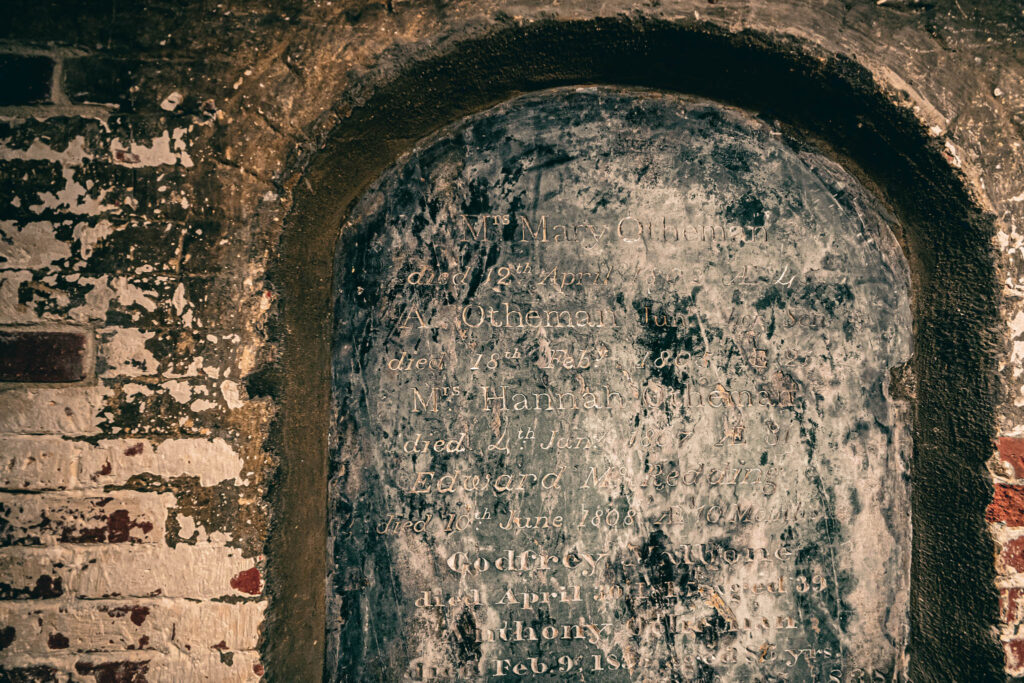

So I here I was in the church, because walking down Salem Street I suddenly realized that in three decades of Boston living that I hadn’t ever bothered to go into Old North — and there didn’t seem to be too many tourists about — and I had with me a camera and a new lens purchased to beat the new tariffs — and so I paid my ten dollars and borrowed the laminated sheet of explanations — and I walked about the nave with its rich-person private box pews and the gallery where they put the poor and the colored and finally into the crypt with its plumbing and tombs — and I took pictures and became more and more anxious about it all. Over the exit was a marble bust of slave-owning Washington (free is me and not thee!) and the laminated guide-sheet noted that the aged Marquis de Lafayette (the one true and failed hero of the Revolution who wasn’t a hypocrite and who wasn’t even an American except through belated honors) had pronounced on seeing it, “Yes, that is the man I knew.”

But it was all in vain. The Revolution came and went, the slaves were still slaves, the free weren’t really free, and this church was funded by those who trafficked in the products of chattel slavery and (of all things) smuggled chocolate. The Civil War for which p-Cousin Henry had written his poem was won and then lost slowly again over the next century and a half, at least judging by the news.

I had walked through the Common to get to the North End earlier in the morning. And as if it was a totally normal thing, a formidable array of helicopter gunships was parked near the all-American national-sport baseball fields along Charles Street, not far from where the British Regulars notoriously would have bivouacked so long ago. But since when did a recruiting drive require so much intimidating firepower? Would a few lanterns in a steeple — or even a poem — do anything against Hellfire missiles?