I am forever grateful that, in those less-xenophobic times in America when I attended Dartmouth College, I was required for my degree to enroll in a certain number of “humanities” classes that were categorized as “Non-Western”, and that my required art and architecture history survey courses substantially referenced the historic cultures of Asia. Not only would half the world been effectively closed off for me without this background education, but I (a white kid who literally grew up in a swamp in the rural American south) would not have the ability to get off an airplane on the other side of the planet, see something, and almost immediately have enough of a grasp of the cultural context to begin to interpret what I am seeing.

So even before first visiting Japan over three decades ago, I knew in a basic sort of way who the Shogun was, as distinct from the Emperor; how Edo became Tokyo following the Meiji Restoration of 1868; and what Shinto is, as compared to Buddhism. Nevertheless, there has been a change in my conception of certain aspects of Japanese cultural history. I somehow had the idea from my education days that the various “military governments” or Shogunates — in particular the last, the the 265 years of the Tokugawa bakufu — were a kind of antiliberal, insular, feudalistic and inescapably sharp-blade-seppuku-brutal interruption in a more legitimate trending Japanese arc-of-progress.

More recently, judging by my reading, the Tokugawa regime seems to have been posthumously — and perhaps, just slightly suspiciously — rehabilitated.

The perennially-popular Ukiyo-e prints, products of the supposedly rigid and closed “feudal dark age”, make it clear that at least at some points and for some citizens, Tokugawa Japan was not an entirely oppressive and regressive pre-modern police state. I can also concede the possibility that many of the most unique (and charming) aspects of Japanese culture developed during the long inward-focused Tokugawa period, when prosperous, exquisitely-refined “floating world” Edo was the de facto political center of the archipelago and the first city on the planet to top a million inhabitants.

Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616), the founder of the dynasty and the last of the Three Great Unifiers of the Japan, clearly understood the necessity for political stability. But did he really have more than his own and his clan’s best interest at heart when he established his rule?

Or am I buying into another culture’s populist revisionism, someone else’s myth of a golden age and a “benevolent” dictator?

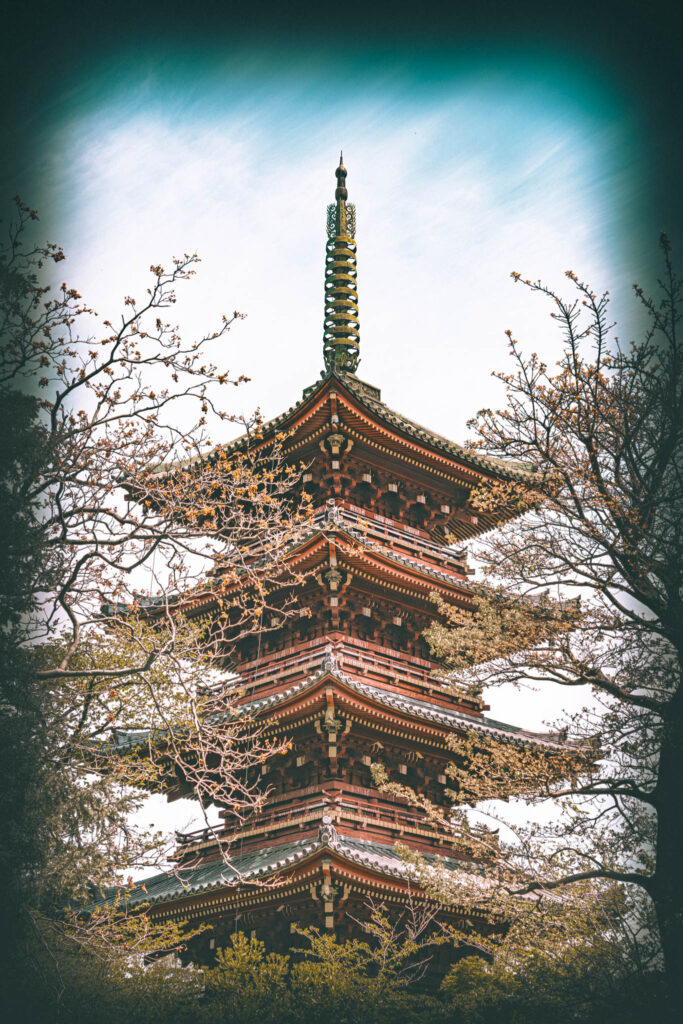

So I was thinking these sort of thoughts today when I visited wildly-baroque Ueno Toshogu, which is dedicated to Tōshō Daigongen, the gongen of Tokugawa Ieyasu. It’s not Ieyasu’s tomb or even monument in the Western sense, per se, a gongen being a type of kami (Shinto deity or spirit) that is also an incarnation of a buddha. The Tosho-gu is thus technically a place of worship. The weary young ladies selling tickets to tourists were dressed in the traditional red and white of miko (Shinto shrine maidens or female shamans), and I must assume they are. And so I must also assume that Ieyasu’s gongen like any other kami in theory resides — divine and unchanging — in the unseen sanctuary of the shrine. (Incidentally, he also dwells in every other of the 130 remaining Tosho-gu in Japan since kami are subject to bunrei, a sort of spiritual mitosis or soul division!)

Ueno Toshogu is one of the few bits of Ieyasu’s city that survived the recurrent devastating fires, the so-called “Edo Blooms”; the fierce 1868 Battle of Ueno between Shogitai Tokugawa revanchists and the newly-constituted Imperial Army of the Meiji Emperor; the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923; and finally the American bombs — 1,665 tons, and filled with inextinguishable napalm not democratic ideals — that reduced so much of what remained of Tokugawa Edo and so many of its terrified Showa-era Tokyo inhabitants to cinders on March 9, 1945 in the single deadliest air raid of the Second World War. Within the grounds of the shrine dedicated to the first Tokugawa shogun, the proponent of political stasis, his Edo (appropriately enough) seems to linger on.

Leave a Reply