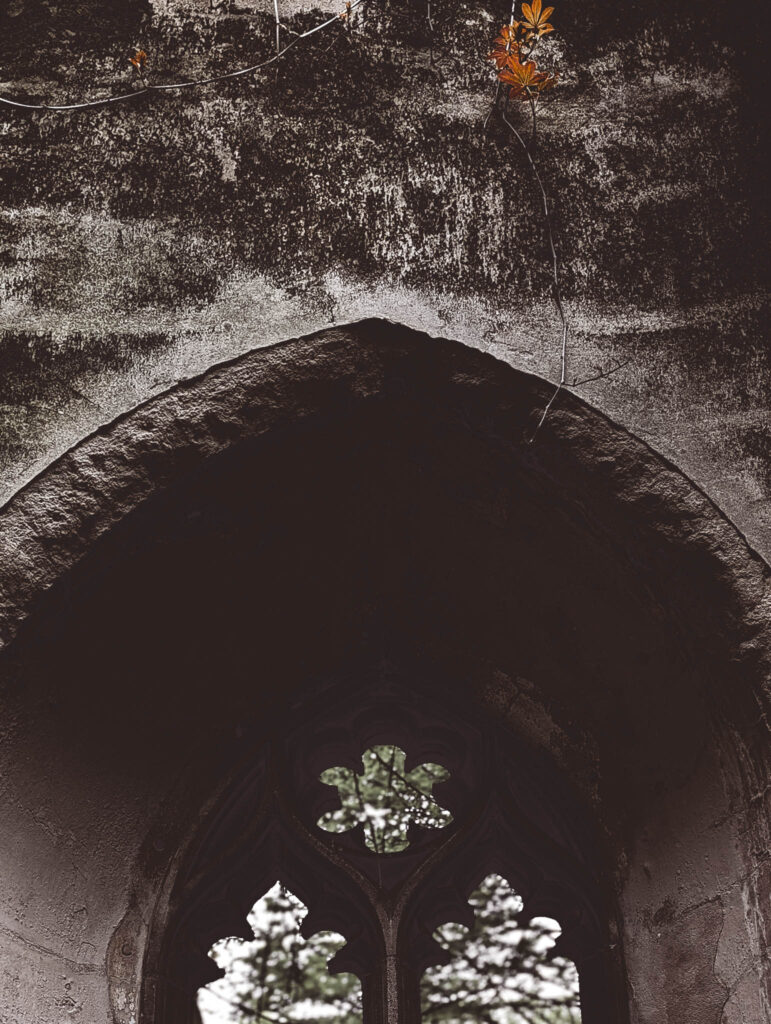

These are actually photos of two different London churches, photographed on two different changeable English days (the 15th and the 18th), but they seem of a piece and so I have decided to deal with them in this single journal post. Christ Church Greyfriars and Saint Dunstan-in-the-East are both Wren-reconstructed edifices (Christ Church was in fact Wren’s second-largest church, after nearby St. Paul’s Cathedral). Both took direct hits from German bombs (in 1940 and 1941, respectively). And both were eventually consigned in their ruined state as roofless shells to become public gardens. Successfully, in fact. Despite the chill April rain and clouds (which might not be obvious from my photos, thanks to the magic of Raw file format processing) both ruin-gardens were occupied during my visits with plenty of happy but slightly-damp young TikTok-ers, coyly posing in front of the empty arches.

Of course, behind the joyful selfies and giggling and the early flowers one perceives a jarring ambience of another sort entirely. “Jack will show you your room: I have given you the room in the tower.” (E.F. Benson, 1912)

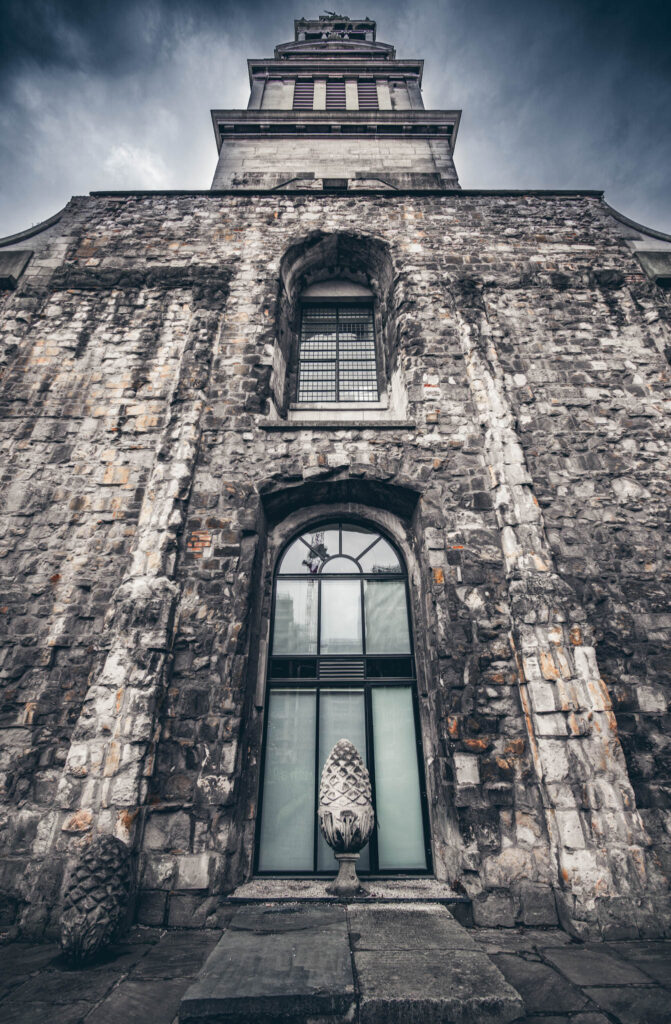

The post-ecclesiastical career of the surviving tower at Christ Church Greyfriars bears discussing. With the steeple by Hawksmoor in 1704 — I assume the term refers to the belfry and above, areas which do have that slightly ominous, not-quite-right Hawksmoor “look” — it was restored in 1960 and used as an office by architects Seely & Paget, who although successful seem chiefly remembered for their partnership and lifestyle (rather gay, in both cases) outside of their practice. Seely and Paget are described in the appropriately melancholy and rather befuddled Bleak Houses: Disappointment and Failure in Architecture by Timothy Brittain-Catlin (The MIT Press, 2014), a book that I purchased in the hope that it might make me feel better about my own abortive career — or at least help me better understand my own dismal lack of achievement.

Finally in 2007 the Christ Church Greyfriars tower was converted to a minimalist, 12-level private residence for a Goldman Sachs banker by architects Boyarsky/Murphy. I cannot imagine the effort and sums of money it must have taken “to smooth out” the various bureaucratic hurdles such a wild change of program entailed. Yet the tower home seems uninhabited as of this writing, having changed hands during the pandemic.

However — also as of this writing — one can review photos of the interior prior to the sale at two websites, a specialty realtor’s <link> and the architects’ <link>. The latter is especially interesting, because it takes the form of a slide show, that ascends from the base to the topmost stair, and includes gritty black-and-white images of the pre-rehabilitation situation. The finished home is very smooth, very high end: white walls, glass-panel railings, shined marble countertops, blond-oh-so-blond sensually-chunky cabinetry. Very few traces, it seems, of sooty baroque masonry intrude into the polish.

It would be hard for a place like this to not be interesting, spatially, as long as your legs could handle the hundreds of steps. But I can’t help but think I wouldn’t have “done it” like this, if somehow it was my project. Where’s the romance, right? It might work for a banker, but what kind of would-be wizard lives within white walls in an oh-so-blond condo (however “vertical”)? Where’s the old oak throne in an otherwise empty round room, which one can encircle if necessary with a chalk-drawn pentacle? Where are the tottering shelves to hold “many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore”, as well as a bust of Pallas for visiting ravens and the skull of the Black Monk (or a plaster copy thereof, like the one I own) to remind one to regularly visit the dentist (among other things)? Where’s the rickety, narrow staircase to Hawksmoor’s freestanding Ionic colonnade, where one might consult the tutelary stars as well as the psychogeographic portents concealed in the layout of King Lud’s streets below?

I suppose that the simple fact that I would pose such rhetorical questions (as opposed to making the sort of the abstracted “valid critiques” that the faculty encouraged at Yale) probably explains my unsatisfying career more than any book I could purchase.

Leave a Reply